SA not geared to go electric.

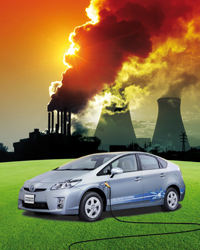

Internationally, auto manufacturers are gearing up for the production of electric cars. But South Africa has bigger problems, which are likely to delay the arrival of silent, eco-friendly, zero-emissions vehicles for at least a few decades.

Theoretically, there is nothing preventing a South African consumer from running an electric vehicle (EV). EVs can charge using the power supplied by the national grid - replacing a high fuel bill with a higher power bill - but there would be obvious limitations.When international customers signed up for the Mini E electric car field trial, BMW popped past their houses and installed a charging receptacle. Even if this were the case in South Africa, real world use - and our high-mileage culture - would quickly show up the limitations of a 200km usable range. An EV would need to be charged every night.

As it is, the country`s power utility, Eskom, is barely able to produce enough power to keep the lights on, without the additional strain of thousands of EVs being charged every night. Unfortunately, government`s strategy to add additional power capacity is murky, at best, and earlier this year talk of rolling blackouts reared its ugly head again.

Meropa Spannerworx motoring analyst Patrick Gearing says it is possible to have cleaner cars that place less strain on the oil supply, but moving the demand to the electricity grid - where there are more immediate shortages - misses the point, especially if consuming more electricity leads to increased harmful emissions.

This is another major hurdle facing the introduction of EVs into the local market. Gearing explains that, even if Eskom could produce enough electricity to handle the additional demand, it operates coal-fired power stations. This means any benefit gained by running zero-emission cars would be off-set by the additional carbon footprint created when charging them.

Ultimately, motoring industry experts predict that South Africans will be able to enjoy zero-emissions motoring, but this won`t happen in the near future. Gearing predicts it will probably be 30 to 40 years before petrol-powered vehicles are completely replaced.

But, while the country is clearly nowhere near being able to facilitate the introduction of EVs, it has not stopped government from placing additional strain on the pockets of local motorists. In December last year, President Jacob Zuma" rel=tag>Jacob Zuma - prior to attending the climate change conference in Copenhagen - announced that the country would reduce its greenhouse gas emissions by 34% by 2020, and by 42% by 2025.

In September, government introduced the carbon tax on cars, with finance minister Pravin Gordhan" rel=tag>Pravin Gordhan announcing this tax as an incentive for people to buy cleaner cars. The tax is imposed on vehicles that produce more than 120g of carbon dioxide per kilometre - every gram above this figure is taxed at a rate of R75 + VAT. The move is an effort to encourage the sale of vehicles with smaller engines, which use less fuel and emit less CO2.

But, according to Nico Vermeulen, director at the National Association of Automobile Manufacturers of South Africa, the money from that tax is going into the general fiscus, not specifically towards any carbon reduction programmes or improvement of the fuel quality.

Meanwhile, National Treasury figures suggest government is likely to earn R450 million from the green tax in the current fiscal year.

DIRTY FUEL

Guy Kilfoil, GM for group communications and public affairs at BMW South Africa, says the country has more immediate concerns at the moment than the installation of an EV charging point in every mall parking lot. He explains that spending money on a sector of the economy that affects such a small percentage of the population, on a day-to-day basis, is not realistic.

South Africa, he says, is in the unfortunate position of being a developing country with first-world needs.

As such, many of the new petrol- and diesel-powered cars available on showroom floors require cleaner fuel than can be provided at local pumps. As Europe starts moving over to ultra-clean Euro 6 fuel, South African refineries are still putting out Euro 2 fuel.

Calculations show that a million cars running on clean, modern fuel would do a lot more good for the environment than 1 000 EVs.

Not only is the country`s fuel "old tech", there is also not enough of it. Local refineries are operating at capacity and, according to latest reports, additional fuel is being imported to meet demand. The current fuel infrastructure, on which the country is heavily reliant, is of primary concern to industry and business, hence the need for the R11 billion oil refinery at the infamous Coega industrial zone (IDZ), in the Eastern Cape. The Coega IDZ has been earmarked as the preferred location for PetroSA`s crude oil refinery, and plans are for this refinery - set for completion in 2015 - to more than meet the country`s demand for clean, modern fuel.

Cleaner fuel will reduce carbon emissions from cars, prompting motor industry observers to question why government did not wait to impose the carbon tax only once the country had access to cleaner fuel.

THE FUTURE

It`s no secret that the world is running out of oil. The finite resources are going to run out, sooner rather than later. To give an idea of how soon, one only needs to look at the latest numbers from the models scientists are using. Taking into consideration the growing oil demand and known reserves, peak oil production will be reached in 2015. The same model predicts reserves to be depleted by 2060.

Additionally, carbon dioxide emissions are the current focus of governments the world over. These gases have been proven to contribute to global climate change and, despite the fact that vehicles are only responsible for 3% of global CO2 emissions, the motoring industry has sharply come under the spotlight.

Together, both of these factors make EVs seem like the future of personal mobility.

However, there are limitations to zero-emissions motoring. The electric car`s development dates back as far as the early 1800s, when the first prototypes used either disposable batteries or electrified tracks, for power.

Engineers soon settled on rechargeable batteries, but the technology was simply not there. Limited battery capacity and sluggish performance from these cars made them less appealing than their petrol-powered counterparts. Ultimately, the internal combustion engine became the accepted means of power for motorcars when road infrastructure improved and towns linked with longer stretches of tar.

ISSUES OF RANGE

The EVs going on sale over the next three years, like the Nissan Leaf and BMW`s Megacity Vehicle, will attempt to solve the problems of range and performance. Both companies have committed for their EVs to have an average usable range of more than 160km per charge. BMW claims a further range for the final Megacity, but at the moment the only hard data it has to offer are figures from the Mini E field trial.

Mini E is a regular Mini Cooper with a 150kW electric motor and 260kg battery pack, where the back seats used to be. The 600-strong fleet of test vehicles has been made available to private customers in countries across Europe, the US and China. To date, the longest journey completed in a Mini E has been 158km, while the average daily trip is 43km. With a usable range in city conditions of 160km, this means the car can go three nights between charges. It`s still far less than the 350-500km achieved in a regular Mini, in the same driving conditions.

Locally, there is also the Joule, from Optimal Energy. This all-South African electric car has a claimed range of 300km and seven-hour charge cycle, and is slated to go on sale in 2012. To date, a running model has yet to be seen and, at the time of going to print, Optimal Energy did not respond to questions.

Range would be less of a consideration if charging times were shorter. Auto manufacturers have already collaborated on standardised connectors and charging protocols for EVs: there are three "levels" of charging, with the first two accounting for regular home outlets, while the third is a specialised high current 480-volt source, capable of faster charging. Nissan`s Leaf, for instance, can be charged to 80% in just 30 minutes when using the latter. A full charge over a regular 240-volt power socket takes eight hours.

Globally, EVs are proving popular, according to customer feedback from the Mini E field trial. Even in situations where the car ran out of power or proved too limiting, the overall sentiment was that this is the way forward. EVs also make perfect sense in a city environment: the stop-start traffic environment in which cars produce the most harmful emissions.

But the future of EVs in South Africa remains unclear. While local motorists may be eager to join the green revolution, this will not happen before some considerable hurdles are dealt with. By then, however, it is not improbable that the nature of personal mobility may have changed completely.

|

Post a comment

|